As China grapples with the rapid aging of its population, lawmakers are now considering raising the country’s retirement age in an attempt to address mounting economic challenges.

But the proposal to delay retirement, which was recently reviewed by China’s top legislative body, has sparked widespread debate and anger. With concerns over youth unemployment, a shrinking workforce, and a pension system at risk of running dry, China is facing an ominous moment in its economic future.

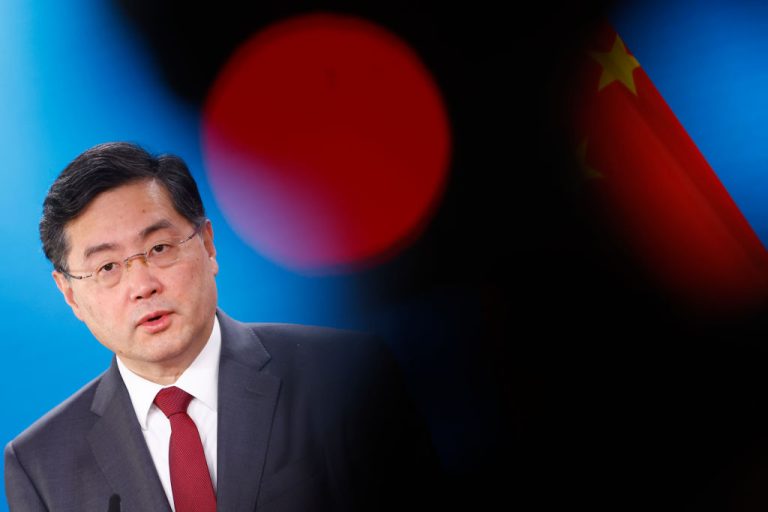

RELATED: Jake Sullivan Meets With Xi in Rare Meeting as Washington Navigates Sino-US Tensions

A shrinking workforce

At the heart of this discussion is the shifting demographic landscape in the country. Life expectancy has risen significantly in recent decades, reaching 78 years as of 2021, and is projected to exceed 80 years by 2050. Meanwhile, the working-age population that supports retirees has been shrinking, with each retiree now supported by five workers — a ratio that could drop to 2-to-1 by 2050.

This imbalance is putting enormous pressure on China’s pension system, which, according to the state-run Chinese Academy of Sciences, may run out of funds by 2035.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

The retirement age in China is among the lowest in the world, set at 60 for men, 55 for women in white-collar jobs, and 50 for women in factory positions. In comparison, many developed countries have set their retirement ages closer to 65. China’s current policy was established when life expectancy was much lower, and now, with millions of people living longer, the system is strained.

“It is an inevitable choice for China to adapt to the new normal of population development,” said Mo Rong, Director of the Chinese Academy of Labour and Social Sciences, as he reflected on the critical need for reform.

Pension deficits

To make matters worse, several Chinese provinces are already experiencing pension budget deficits. According to data from the finance ministry, 11 of the 31 provincial-level jurisdictions are running in the red. Extending the retirement age could alleviate some of this financial strain by delaying pension payouts, while also keeping older workers in the labor force for a longer period. But experts are also noting that the solution comes with its own set of challenges.

The Chinese Academy of Labor and Social Sciences emphasized that reform is urgent. National health authorities have projected that the number of citizens aged 60 and older will rise from 280 million to over 400 million by 2035. This rapid increase in the elderly population is comparable to the combined populations of Britain and the U.S., underscoring the sheer scale of the issue.

Meanwhile, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced in July that it would gradually raise the retirement age, but the specifics of this plan remain under review. Draft changes to the law are expected to be made public for feedback in the coming weeks, and lawmakers are carefully considering the impact of these changes on both the elderly and younger job seekers.

RELATED: China’s Youth Unemployment Crisis Spurs Rise of ‘Rotten-Tail Kids’

Tension between generations

One of the most prominent concerns surrounding the reform is the impact it could have on an already struggling job market. Youth unemployment has become a pressing issue in China, and many citizens fear that older workers staying in their jobs longer will only exacerbate the problem. This sentiment has been echoed widely on Chinese social media platforms.

“Young people cannot find jobs, middle-aged people are worried about being laid off, and now there is another problem: the elderly can’t retire,” said one Weibo user (a popular blogging site in China) in response to the discussions in Beijing.

While the public’s apprehension is understandable, experts argue that the retirement reform is unlikely to pit older workers against young job seekers for the same positions. “It’s a different set of jobs that older people are going to be keeping on, blue-collar and white-collar jobs which will be different to entry-level ones,” said Stuart Gietel-Basten, professor of Social Science and Public Policy at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Still, China’s economy, like many others, has seen structural shifts in its job market. In particular, with automation and technology reducing the availability of traditional blue-collar jobs. This has left many young workers struggling to find stable employment.

RELATED: Asia’s Wealthiest Woman Loses $12 Billion in China’s Real Estate Crisis

In addition, the rising cost of living and housing in urban areas has placed further pressure on young people to secure well-paying jobs quickly. Many now fear that prolonging the careers of older workers will reduce their opportunities to move up the career ladder or secure positions that offer long-term stability.

The road ahead

Countries like Japan and South Korea, which have also faced aging populations, have successfully raised their retirement ages to 65 and 63, respectively, in response to rising life expectancies. These countries offer potential models for China to follow, though there are significant differences in how pension systems and employment laws function across regions and industries.

In China, the challenge is further complicated by disparities between rural and urban areas, as well as among different provinces. Migrant workers and those engaged in gig work, for example, often face inconsistent access to pensions due to frequent movement between jobs.

“When you look purely at life expectancy, it should be raised, but it’s got to be done in a fair way,” said Gietel-Basten, adding, “Particularly if you are a migrant or gig worker who has moved around and may not get those years paid in.”

As China’s population continues to age and its workforce shrinks, reform is becoming increasingly necessary. The balancing act for lawmakers will be to implement these changes in a way that addresses both the immediate economic concerns and the broader social implications, notes Mo.

China must “adapt to the new normal of population development,” he said. Whether through gradual reforms or more drastic measures, the country is at a crossroads, and how it navigates this moment will shape its economic future for decades to come.