The interaction between a chemical slurry and ancient shale during hydraulic fracking is producing radioactive waste, according to Dartmouth College research. The study, detailed in twin papers appearing in Chemical Geology, is the first research that characterizes the phenomenon of radium transfer in the widely-used method to extract oil and gas.

The findings add to what is already generally known about the mechanisms of radium release and could help the search for solutions to challenges in the fracking industry. As a result of fracking, the U.S. is already a net exporter of gas and is poised to become a net exporter of oil in the next few years. But the wastewater that is produced contains toxins like barium and radioactive radium.

Upon decay, radium releases a cascade of other elements, such as radon, that collectively generate high radioactivity. Mukul Sharma, a professor of earth sciences at Dartmouth and head of the research project, said:

“The stuff that comes out when you frack is extremely salty and full of nasties.

“The question is how did the waste become radioactive? This study gives a detailed description of that process.”

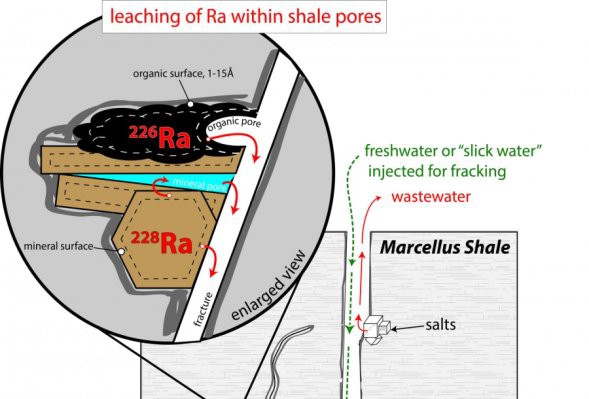

During fracking, millions of gallons of water combined with sand and a mixture of chemicals are pumped deep underground at high pressure. The pressurized water breaks apart the shale and forces out natural gas and oil. While the sand prevents the fractures from resealing, a large proportion of the so-called “slick water” that is injected into the ground returns to the surface as highly toxic waste.

In seeking to discover how radium is released at fracking sites, the research team combined sequential and serial extraction experiments to leach radium isotopes from shale drill core samples. For the study, the research team focused on rocks taken from Pennsylvania and New York locations of the Marcellus Shale. The geological feature is one of the major rock formations in the U.S. where fracking is being carried out to extract natural gas.

The first research paper found that radium present in the Marcellus Shale is leached into the saline water in just hours to days after contact between rock and water are made. The leachable radium within the rock comes from two distinct sources, clay minerals that transfer highly radioactive radium-228, and an organic phase that serves as the source of the more abundant isotope radium-226.

Fracking draws radium from fractured rock

The second study describes the radium transfer mechanics by combining experimental results and isotope mixing models with direct observations of radium present in wastewaters that have resulted from fracking in the Marcellus Shale. Taken together, the two papers show that the increasing salinity in water produced during fracking draws radium from the fractured rock.

Prior to the Dartmouth study, researchers were uncertain if the radioactive radium came directly from the shale or from naturally-occurring brines present at depth in parts of the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania. Joshua Landis, a senior research scientist at Dartmouth and lead author for the research papers, said:

“Interaction between water and rock that occurs kilometers below the land surface is very difficult to investigate.

“Our measurements of radium isotopes provide new insights into this problem.”

The research confirms that as wastewater travels through the fracture network and returns to the fracking drill hole, it becomes progressively enriched in salts. The highly-saline composition of the wastewater is responsible for extracting radium from the shale and for bringing it to the surface. Sharma said:

“Radium is sitting on mineral and organic surfaces within the fracking site waiting to be dislodged. When water with the right salinity comes by, it takes it on the radioactivity and transports it.”

The Dartmouth findings come as oil and natural gas production in the U.S. have increased dramatically over the past decade due to fracking. Understanding the mechanics of radium transfer during fracking could help researchers develop strategies to mitigate wastewater production. Sharma added:

“The science is being left behind by the gold rush. Getting the science is the first step to fixing the problem.”

An earlier Dartmouth study found that the metal barium reacts to fracking processes in similar ways. Radium and barium are both part of the same group of alkaline earth metals.

Provided by: ScienceDaily [Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.]