As China continues to grapple with a sputtering national economy, a new phenomenon has emerged within its workforce — “rotten-tail kids” — a term coined to describe young college graduates forced into low-paying jobs, or having to live off their parents’ pensions due to a lack of work opportunities.

This social shift, which is rooted in a sharp rise in youth unemployment, has left millions of young people disillusioned with the promise that a college degree once held.

The phrase “rotten-tail kids” is reminiscent of “rotten-tail buildings,” a term used to describe the millions of unfinished homes that have plagued China’s economy since 2021. Now, it symbolizes the plight of college graduates who are unable to secure meaningful employment in a labor market hampered by the lingering effects of zero-COVID controls, regulatory crackdowns, and a struggling economy.

RELATED: In Rare Admission, Xi Jinping Says China’s Economy Is Struggling

A pessimistic job market

The job market for young Chinese graduates is more competitive and uncertain than ever. In July 2024, the youth unemployment rate spiked to 17.1 percent, reflecting the challenges faced by the 11.79 million college students who graduated this summer. This surge in unemployment follows a troubling trend, with the jobless rate for Chinese youth aged 16-24 reaching an all-time high of 21.3 percent in June 2023.

Success

You are now signed up for our newsletter

Success

Check your email to complete sign up

In response, officials halted the publication of unemployment data to reassess how these figures were compiled, but the reconfigured numbers paint an equally bleak picture.

The situation has left many young graduates questioning the value of their education. “For many Chinese college graduates, better job prospects, upward social mobility, a sunnier life outlook — all things once promised by a college degree — have increasingly become elusive,” said Yun Zhou, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Michigan.

This sentiment is also echoed by many young people who have returned to their hometowns, becoming “full-time children” dependent on their parents’ pensions. The phenomenon has sparked widespread concern, as it not only reflects the difficulties faced by the younger generation in securing stable employment but also places additional financial and emotional burdens on families, particularly in a society that values self-reliance and upward mobility.

RELATED: Here’s Just How Badly ‘Zero-COVID’ Has Damaged China’s Economy

Limited options

The economic landscape has forced young people to make difficult decisions. With fewer high-paying jobs available, many are accepting positions far below their qualifications or simply opting out of the job market altogether.

Some, like 27-year-old Zephyr Cao, who holds a master’s degree from China Foreign Affairs University, have even given up on job hunting after realizing that the wages offered are not commensurate with their education. “If I worked for three or four years after my undergraduate studies, my salary would probably be similar to what I get now with a master’s degree,” Cao told Reuters, as he reflected on the widespread disillusionment among his peers.

Cao, who has returned to his home province of Hebei, is considering pursuing a PhD in hopes that his prospects will improve in a few years. However, the uncertainty of the job market makes this a risky bet. Even for those with degrees in high-demand fields, securing employment is far from guaranteed.

Shou Chen, a third-year student majoring in artificial intelligence at Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, has struggled to find an internship despite her field being considered a key area of growth. “It may be worse,” said Chen, expressing concern that an oversupply of graduates in her field could exacerbate the problem.

An uncertain outlook

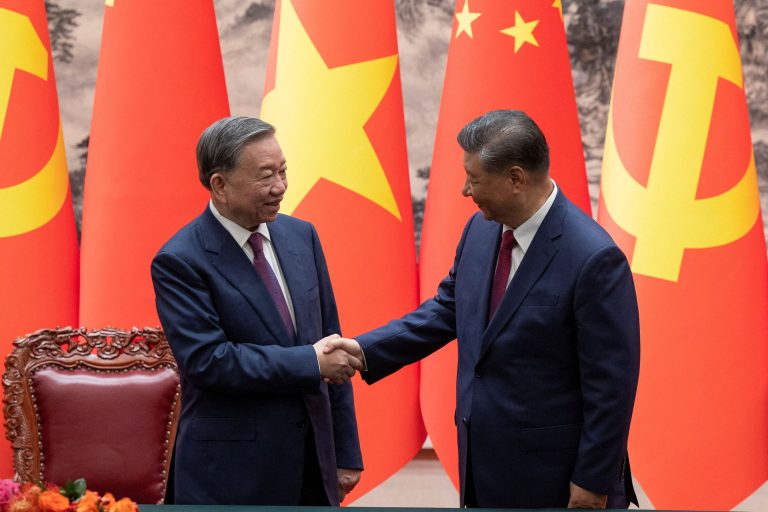

Meanwhile, the Chinese government has recognized the severity of the youth unemployment crisis, with leader Xi Jinping emphasizing on several occasions that finding jobs for young people is a top priority.

In hopes of tackling the crisis, Beijing has implemented measures such as organizing job fairs and rolling out business policies to boost hiring. But these efforts have yet to make a significant impact on the ground, as the number of graduates continues to outstrip the available jobs.

The roots of this issue trace back to 1999, when China expanded university enrollment to produce a more educated workforce for its rapidly growing economy. While this strategy initially worked, it has since led to an oversupply of graduates — a problem that authorities first acknowledged in 2007. Despite various efforts to address the issue, the gap between the number of graduates and available jobs has persisted and even widened in recent years.

RELATED: China’s Birth Rate Hits a New Low, Population Falls by 2 Million

Looking ahead, the outlook remains uncertain. A study published in June by China Higher Education Research — a journal under the education ministry — predicts that the supply of tertiary students will exceed demand from 2024 through 2037. This imbalance is expected to persist until declining fertility rates finally reduce the number of new graduates entering the workforce.

The study also projects that the number of college graduates will peak at around 18 million in 2034, raising questions about how the economy will absorb such a large influx of educated young people.

For millions of young Chinese, the promise of a college degree leading to a better life is slipping away, leaving them to navigate an uncertain future in a labor market that shows no signs of improving. The government’s efforts to address this crisis will need to be far-reaching if they are to prevent a lost generation of highly educated but underemployed youth.